Cities for women, by women

Happy Cities Senior Housing Expert Paty Rios gets real about what — and who — it takes to design inclusive cities.

Paty Rios has often been one of only a few young women working amidst a sea of gray-haired men. But at 35 years old, the Mexico-city based architect and designer is noticing incremental changes that suggest the industry is inching closer to gender equity. And she wants to be part of the movement.

Emma Jones, our communications coordinator, talked with Paty about enabling female leadership at work, designing cities that centre all women’s needs, and how she’s using her own platform to amplify other women’s ideas.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Emma: Let’s talk about your experience being a woman in architecture and planning. What is drawing you to centre gender in some of the work you’re doing now?

Paty: Gender has always been on my mind: When you decide to study something, like architecture, that’s dominated by older men, you feel like each step of your career, you have to be overcoming barriers. For instance, just trying to appear knowledgeable and have people listen to you at a construction site — when usually it’s going to be an older male architect doing that — is hard.

When I was working in architecture, I was surrounded by men with really strong voices. I worked in a well recognized international studio, and there were four women and 18 men, or something like that. The ratio was always overwhelming.

This is changing, though, little by little. Lately I see women raising their voices about so many different issues; the frame of the city is just one of them. They’re working to get equitable access to jobs, not have to choose between having a family and a fulfilling career, and make sure they can just walk around the city without feeling like someone is going to molest them.

For me, specifically, it’s this combination of events that are happening in my city and my environment, and then having conversations with my girlfriends about trying to move up the workplace ladder. I’m 35 years old, and the last year or two has been the first time that I feel people are starting to hear me: not just that I’m filling a quota, but that I have gained the experience required for people to hear me. So I’m using this privileged place that I have earned — and my teammates have supported — so that I can speak for the women who don’t have a voice in their discipline or in the workplace.

Emma: A study found only three of the world’s 100 biggest architecture firms are headed by women, and women only hold 10% of the highest ranking jobs at those firms. 16 firms have no women at all in senior positions. How can we support women, not just to choose paths like architecture, urban design and planning, but also to be able to take leadership in them?

Paty: For a while, I was against filling quotas, because I didn’t understand really what was underneath this idea. But the more I have these conversations, the more I realize that we need quotas to ensure that women are going to have the same opportunities to occupy seats at the table.

Next, we need to make sure there are family-friendly policies. There are so many women that are well-prepared, and hitting an age where they are able to lead in decision-making roles, then they have to choose between their career and having a family. I find that’s the breaking point.

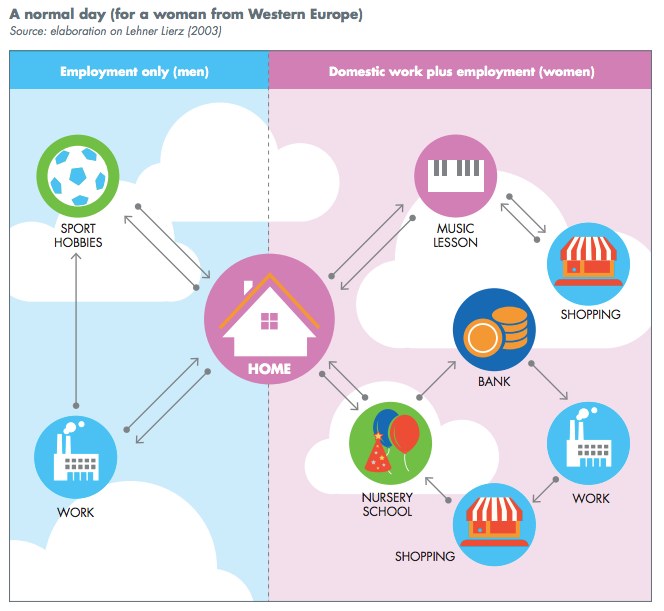

At the same time, from an urban perspective, we should study the patterns of women. If women are working but still taking care of more things in the household than guys, then we need to make sure that they can easily get the things they need near where they work: making sure there is a supermarket close, a daycare, a doggy care, even a place to take a yoga class. All these things need to be close and accessible to the workplace so that women know that that’s their hub, and it can feel like a second home.

This graphic from Civitas identifies gendered differences in commute patterns.

(Source: http://www.busandcoach.travel/download/Maria/civ_polan2_m_web.pdf)

Emma: What does it really mean to design a city for all kinds of women?

Paty: The process needs to change around how we design cities. We need women in leadership positions, that’s one of the first approaches.

The second is we need to start thinking about community engagement in a different way. Usually community engagement events are highly populated by seniors and white men. Again, we are not thinking about the schedules of a woman and what is going to be more suitable for her. Is she going to be able to come to a meeting?

When Happy City was assessing major parks in Mexico City, initially we had developed activities just for teenagers, adults and seniors. However, we knew that most of the people who go to the parks are families. So we turned it into a more inclusive engagement process, where kids could give input in their own ways. That way there would be people taking care of them, and then parents would be able to participate.

The third thing is that we need to ask more questions. Right now, everyone is in love with data. Yes, data is important, however, the way data is collected now is predetermined by systems and the structures that are designed by and built for men. Commute data, for example, doesn’t account for the existing barriers that prohibit women from working, nor does it consider the non-work trips that women are more likely to need.

If we don’t stop and ask women what they want and how the structures should be changed, then we risk moving further in the wrong direction.

Emma: We’re still playing catch up in terms of designing cities for women, even those who are able-bodied, cisgender, and white. How do we work within a more inclusive framework?

Paty: What I know is that starting to include the gender lens into the conversation about cities is an opportunity to be inclusive. This means an intersectional approach. While different people are going to have different needs, it’s about making sure nobody gets left out.

Emma: Something cool happened recently. You posted on Twitter, asking for ideas about how urban design and policy can be more inclusive to women. Can you talk about what happened when you asked your community for input?

Paty: I was very surprised. It was incredible, the amount of women from all over the world that were posting responses. Usually my Twitter account is more linked to what’s happening in Vancouver, so all my contacts are in there.

But suddenly, I started seeing that there were people commenting from Germany, Switzerland, and Finland or Sweden, and somehow it came back to Mexico. This subject was linking people all around the world.

It was interesting to see differences in what women around the world are asking for: in Mexico and Latin American countries, women were asking for light and surveillance, to avoid hot spots where they can be mugged or something else can happen. Then in Vancouver and more developed countries, they were looking at bike lanes, making sure public transit is connected, making sure there are spaces — playgrounds for example — where they can also have meetings.

Usually on social media you expect to have negative criticism. This thread was so positive, transparent and full of ideas.

Hear Paty discuss these topics alongside Saskia Sassen at the Women’s Forum for the Economy & Society in this video: