Why math and rigid rules aren’t enough to build great cities

Photo credit: trip101

Urban planners and architects have long sought clear rules to guide urban design. For every rule about good urban design, however, there are places that offer exceptions. This might make you think that human preferences are random or unknowable. Not so fast.

Consider one popular rule of thumb, called enclosure. People tend to enjoy spending time on streets where the buildings are roughly three quarters as tall as the space is wide.

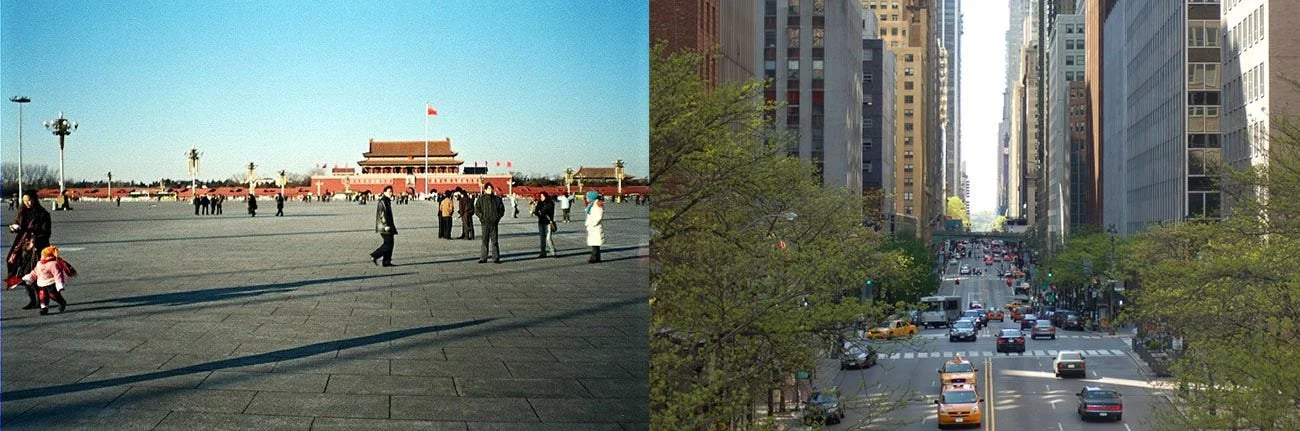

The two examples below show why this matters. If a space is way too wide for its buildings, they offer no clearly-defined sense of space. If buildings are way too tall for their space, they can loom over people and feel oppressive.

Left: photo of Tiananmen Square (Photo credit: Paul Louis). Right: photo of 42nd Street in New York (Photo credit: David Brooks)

The height-width guideline is a successful and important tool for creating people-friendly places. And yet, there are exceptions that bring the rule into question.

St. Peter’s Square is many times wider than its buildings are tall, but it feels reasonably human scale and provides a strong sense of space. Meanwhile, the buildings in many medieval alleyways are many times thinner than their buildings are tall, but they don’t feel oppressive. They’re charming.

Please note: someone made this insightful comparison in a blog post I read years ago. Please help me attribute the author if you know the source. Thank you! (Left photo credit: vgm8383, right: Miguel Virkkunen Carvalho)

How can the height-to-width ratio be so successful in creating great places so often, yet be so wrong in these examples?

All urban design guidelines face some kind of exception like this. This does not mean, however, that all human preferences are just random and unknowable.

Exceptions aren’t exceptional

Let’s play a game that will shed some light. Can you tell which of the four animals below are dogs?

Okay, now make a list of all the rules you use to figure it out. Try to think of rules that, together, will give you the right answer every time without exception.

If you’re struggling, it’s because there are none. Instead, our brains recognize animals (and nearly everything else)based on patterns of traits that tend to clump together. Our brains use something more akin to statistics than rigid rules for this job.

And that’s a good thing. If we depended on simple rules like, “dogs have long snouts,” a single exception could confuse us. And we might mistake a fox for a dog.

Researchers find we use this kind of pattern recognition for understanding language, text, people’s intentions, sequences of events, and lots more. It’s fundamental to how the brain works. As neuroscientist Jeff Hawkins writes, “brains are pattern machines.”

We use the same machinery to process how streets and public spaces make us feel. Even with no clear, rigid rules to guide us, our brain recognizes instantly whether we’re in a place that makes us feel comfortable — and that others will like as well.

Rules only approximate patterns

St. Peter’s Square and medieval alleys can break the rules because our brain doesn’t just measure a ratio and then apply the rule. Texture, colour, entrances, windows, and other details all change how we process a space — just as the brain processes all the features of an animal together when we identify it as a dog.

Consider these two alleys. If the buildings in both were precisely the same height, the ones on the left would still feel more imposing and out of scale. Attributes like visual variety can change how big a wall looks or how a space feels.

(Left photo credit: Siarhei Plashchynski on Unsplash. Right: Miguel Virkkunen Carvalho)

We should make more nuanced guidelines to capture such details, where possible. However, we should also be humble and realize we cannot capture them all. So how do we build people-friendly cities if there are exceptions to all our rules?

Managing exceptions

The best solution is to continue using guidelines while paying careful heed to their limitations. Many guidelines are quite successful in approximating what kind of place people tend to like. Most great public spaces do have a reasonable height-to-width ratio.

That’s especially true because, whether we like it or not, cities are shaped by rules. If we must have bylaws, zoning, and regulations, it’s better if they roughly match real human preferences. As Jeff Speck writes, “The built environment is the output of rules… You can’t fight rules with patterns, so rules it is.”

Achieving excellence

To create truly excellent places, however, urban designers need more than rules. Luckily, we all have one tool that can do the job.

Consider the photos below. Which of these do you think will attract people?

(Top left photo credit: Siarhei Plashchynski on Unsplash. Bottom left: photo by Mac Glassford on Unsplash Bottom left: photo by Nyttend. Top right: photo by anonymous)

That likely took you half a second. How did you know? No computer exists today that could process all the nuances and patterns in those photos as quickly as you just did. At least for now, the only thing for this job is the human brain.

What you just did is a skill, and it is a skill you can become better at. If we study objective evidence on what kinds of places successfully attract people, and those that don’t, we can develop a stronger capacity for recognizing people-friendly places — and how to design them. It’s a skillset practitioners dearly need, yet few planning or architecture programs offer this training in any rigorous way. That needs to change.

(For a nerdy footnote on this skill, and its connection to language philosophy, click here).

Exceptions exist for rules, but human preferences are real

Where there may be exceptions to every urban design rule, there is, however, remarkable consistency in the kinds of places that tend to attract people. Not everyone would prefer Buchanan Street in Glasgow (pictured, left) over a parking lot, but most people would. The proof is in the footprints.

(Left photo credit: Artur Kraft on Unsplash. Right: yiyiwuliu on Unsplash)

Urban designers and decision-makers will make better decisions if more of them are trained in the skill of recognizing people-friendly places. This means developing a detailed familiarity with the places that attract people and those that don’t, strengthening their tacit knowledge for what works and what doesn’t.

Rules remain important. Guidelines help people learn to recognize and create great places. Regulations can prevent the worst excesses, such as giant blank walls or oversized streets. And anyways, rules govern our cities, so we must ensure they don’t prevent good design.

Rules alone, however, are not enough to design the best-possible streets for supporting human wellbeing. We must also train our brains to recognize how millions of small design choices can add up to a place that makes humans happy. It’s something only our brains can do. We should use them.