How Build Canada Homes can go beyond affordability

What Canada can learn from non-market housing communities about social connection, health, and belonging.

Accessible picnic tables, patios, and community garden beds invite residents to connect at Timbre & Harmony, a new non-market housing community in Vancouver. (Brightside Community Homes Foundation)

The homes we live in can make or break our connections with neighbours—with lasting impacts on health, happiness, and belonging.

In September, the federal government announced the Build Canada Homes program, a national initiative to “build affordable housing at scale and at speed.”

This investment is long overdue: Canada’s non-market housing sector lags well behind other OECD countries, comprising just 3.8 per cent of our housing system (compared to 16 per cent in the U.K., for one).

We need more affordable homes, period. But how buildings are designed and managed matters.

Over several years, we’ve been documenting examples of multi-unit homes that strengthen neighbourly connections, belonging, and health. Through numerous studies, we’ve found that people build community in sometimes unexpected places—like lobbies, hallways, and even elevators—and that the design of shared spaces influences how likely people are to interact in them. We’ve learned that residents feel less lonely in community-oriented housing. And we’ve seen that trust and dignity are essential ingredients for deeply affordable housing.

Social connections are not just nice to have. They are the building blocks for resilient, trusting communities, and may extend our lives by 15 years. As Canada seeks to expand housing construction, three new, non-market buildings in Metro Vancouver offer inspiration for more affordable—and connected—homes.

1. Móytel Lalém

Indigenous artwork, balconies, and multiple colours and textures decorate the front facade of Móytel Lalém. (Happy Cities)

Street entrance to Móytel Lalém. (Happy Cities)

Reconciliation through cross-cultural connections

Móytel Lalém is a Halkomelem phrase that translates to “help each other” and “house.” It’s the apt name of a new six-storey building in New Westminster, which provides 96 affordable homes for urban Indigenous and Swahili-speaking people, strengthening community and belonging through deep commitments to equity and reconciliation.

Móytel Lalém stands on the former site of six single-detached houses, on the unceded territory of Halkomelem-speaking Peoples and the Qayqayt First Nation. It’s jointly operated by Lu’ma Native Housing Society and the Swahili Vision International Association, who formed a unique partnership to bring the project to life.

Lu’ma has operated non-market housing for the urban Indigenous community for over 40 years, and recently expanded into building new homes through its development arm, the Aboriginal Land Trust (ALT).

Lu’ma has a long waitlist of people seeking affordable homes. But the organization also wants to help build capacity for smaller non-profits to develop housing. So Lu’ma reached out to Swahili Vision with the idea of a building that could support both Swahili-speaking and Indigenous people.

Together, Lu’ma, ALT, and Swahili Vision designed the building around a social heart: a shared lounge with a kitchen, dining space, and wide doors that open onto the backyard and terrace.

Ground floor social spaces at Móytel Lalém, with common areas in yellow and circulation spaces in blue. Indoor and outdoor shared spaces directly connect to the building’s entryway. (Illustration by Happy Cities, adapted from drawings by RLA Architecture)

These shared spaces facilitate communal activities—from meals, to skill-building workshops, to cultural performances, gardening, and more. Lu’ma also employs a cultural programming coordinator to run activities in all of its buildings, recognizing the importance of these spaces for helping Indigenous residents (re)connect with their cultures, heal, and build relationships with neighbours and Elders. Together, the shared spaces and activities at Móytel Lalém help build connections among this unique community of newcomers and long-time residents alike.

Above: Móytel Lalém opens onto a shared back garden for socializing, playing, hosting events, and more. Balconies and semi-private, ground-level patios connect individual homes to shared spaces while maintaining privacy. (Graphic by Happy Cities, photo by Lu’ma Development Management)

Below: The opening ceremony for Móytel Lalém was hosted in the shared back garden and patio area. (Hey Neighbour Collective)

A lesson in strong policy

Móytel Lalém fills a critical need for culturally appropriate, affordable housing. It received funding from all three levels of government—federal, provincial, and municipal. But not everyone agreed on where this project should be built.

Like many multi-storey, affordable housing projects, Móytel Lalém faced vocal public opposition, particularly at the public hearing. Many people said that the project was a good idea—just not in their neighbourhood.

“The finest things that were said about this project were written by people who had sent in hundreds of letters against it,” said Hugh Forster, one of the project developers.

“[The letters] said, ‘We think affordable housing is an awesome idea,’” said Forster. “‘We think that reconciliation should happen.’ ‘We think embracing the Swahili community is a great idea.’ Second paragraph: ‘But don’t build it here.’”

Despite this vocal opposition, New Westminster Council unanimously approved the project, for two key reasons.

First, the City learned through its public engagement process that those who opposed the project were a minority. There was vast community support outside of the public hearing, with Forster sharing that Móytel Lalém "smashed [the City’s] records for support letters.” Second, the project aligned with New Westminster’s Strategic Plan, which stated clear priorities to support affordable housing as well as reconciliation, inclusion, and community engagement.

Since moving in in 2024, residents feel the impact of a home designed for social connection.

“We don’t feel alone here,” said one resident in an interview with Radio-Canada. “If we cross paths in the elevator, we say hello, we say good morning. It’s a very friendly community. I feel like I’m at home a little bit.”

Under new legislation in B.C., projects that align with a city’s official community plan will no longer be required to hold a public hearing. More than ever, long-term plans that prioritize equity and affordability—and that legalize six-storey housing throughout all neighbourhoods—will help make it easier to create more homes like Móytel Lalém.

2. Vienna House

Rendering of the entrance to Vienna House, through a shared courtyard. (Public Architecture)

During the early planning stages for Vienna House, the design team assessed two different building forms: an O-shaped building with a courtyard, versus a more typical J-shaped building.

Although the “J” form had a slightly lower capital cost, the “O” shape won out on almost all other measures: It supported better livability, relied less on HVAC (notably, lowering the costs of cooling the building by two thirds), was more climate resilient, had better acoustics, and provided greater overall value to the owner and residents.

Ground floor social spaces at Vienna House, with common areas in yellow and circulation spaces in blue. Residents pass through the courtyard travelling to and from their front doors, creating more opportunity for social encounters. (Illustration by Happy Cities, adapted from drawings by Public Architecture)

It was also more social. Analysis from the FLUID Sociality tool, which predicts the number of social interactions that residents will have as they move through a building, found that the “O” scheme could generate 57 per cent more encounters and 35 per cent more greetings than the “J,” simply due to the building’s layout. Over time, these regular encounters help neighbours build familiarity, creating opportunities for friendship and mutual support. In short, the courtyard “O” building was both more resilient and more social.

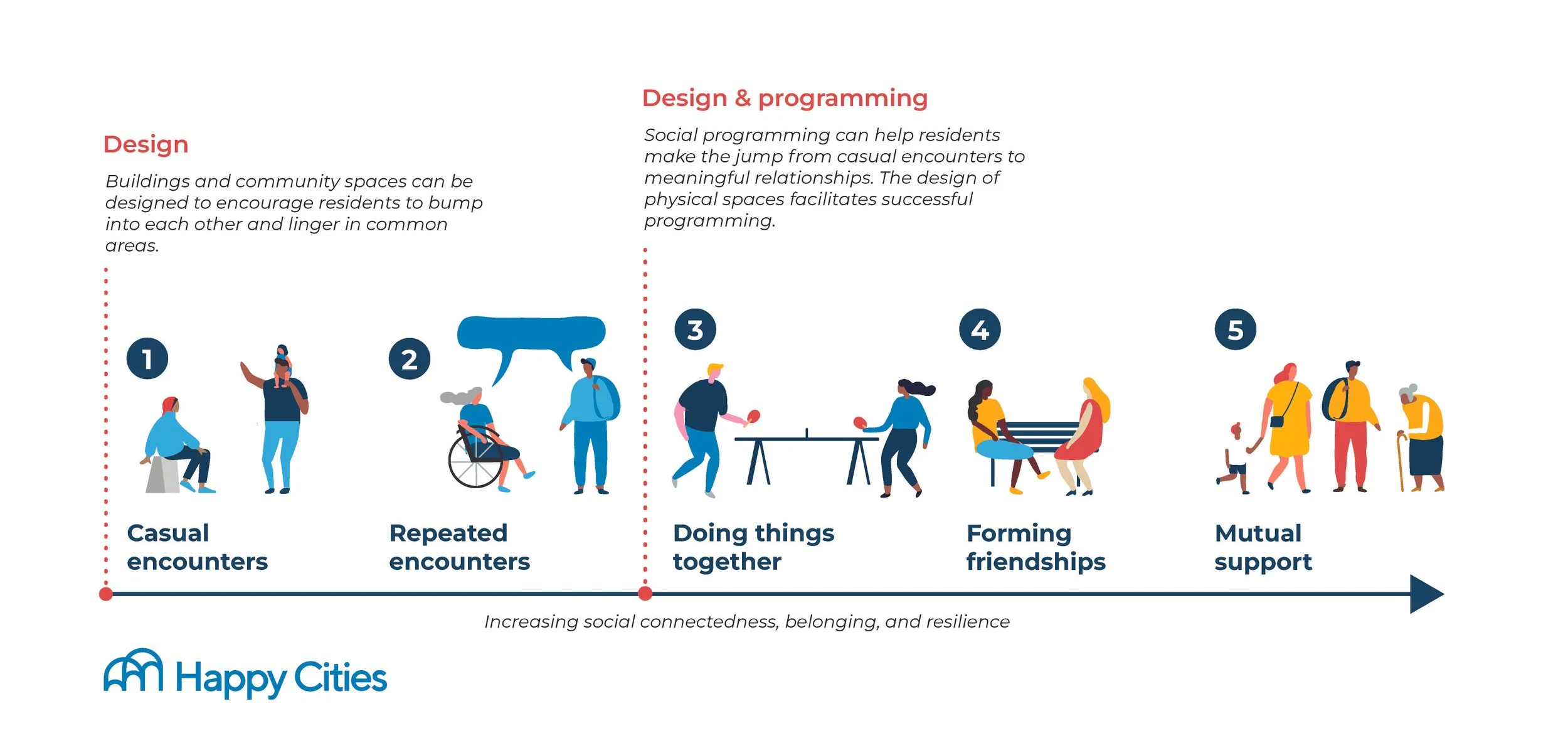

Regular encounters and shared activities help neighbours build deeper relationships and mutual support over time. (Happy Cities)

Setting a new standard for climate-resilient, non-market housing

Vienna House has a counterpart called “Vancouver House” in Vienna, Austria. The two projects aim to implement and test best practices for net-zero emissions buildings.

Vienna House uses a combination of wood frame construction, prefabricated components, and Passive House design to reduce its carbon footprint. The City of Vancouver partnered with BC Housing to develop Vienna House, which will be operated by More Than A Roof Housing Society. The City also provided land for the project, reducing a major cost.

At Vienna House, homes are placed along one side of the outdoor walkways, which overlook the courtyard. This layout allows all homes to have natural light and airflow on both sides, lowering cooling costs and creating more inviting living spaces. The outdoor walkways include social nooks—small patio areas with chairs and other furniture that invite people to linger, chat with a neighbour, or read a book while kids play below.

The courtyard at Vienna House is designed to be the social heart of the community, with space for planned events and informal socializing. (Graphic by Happy Cities, illustration by Public Architecture)

Once Vienna House is complete, More Than A Roof plans to offer monthly community meals, volunteer opportunities, skill-building workshops, and other regular social events to help residents build community in their new home.

3. Timbre & Harmony

Aerial view of Timbre & Harmony, two non-market buildings in Vancouver connected by a shared pathway and outdoor gardens. (Brightside Community Homes Foundation)

Redeveloping aging buildings to provide healthier, more connected homes

Across the Lower Mainland, many older rental and affordable buildings are in need of upgrades. Some pose serious barriers to accessibility, directly impacting the health and wellbeing of aging residents or those with disabilities.

Brightside Community Homes Foundation is a non-profit housing provider with a goal to double the number of affordable homes it provides over the next 10 years. The organization has embarked on a retrofitting program to achieve net-zero carbon emissions across its portfolio, and recently redeveloped four of its older properties to better support wellbeing for residents. Combined, these four sites will provide nearly 500 homes—compared to only around 200 total in the previous buildings.

One of the new developments, Timbre & Harmony, includes two buildings, replacing the 57 prior units with 157 new affordable, secured rental homes designed primarily for older adults and people with disabilities.

Age-friendly, accessible, climate-resilient housing

Social spaces support wellbeing at all ages, but can be extra important for older adults to maintain community connections and stay active—both of which support long-term health and aging in place. The two buildings at Timbre & Harmony open onto a shared outdoor garden, filled with a variety of vegetation, accessible community planter boxes, benches, and picnic tables. Balconies and ground-level entryways face onto a wide pathway between the two buildings, co-locating social spaces with the places that people pass through every day.

Ground floor social spaces at Timbre & Harmony, with common areas in yellow and circulation spaces in blue. Indoor and outdoor shared areas form a connected network, increasing the likelihood of residents bumping into one another. (Illustration by Happy Cities, adapted from drawings by Ryder Architecture)

On a recent walk through the new buildings, we bumped into a resident standing in his outdoor doorway, and asked him how he liked his new home.

“It couldn’t be nicer,” he said, grinning and gesturing to the shared patio area that his home opens onto. “This is my front yard.”

The pathway through the centre of Timbre & Harmony doubles as a social garden area, with glass doors into the shared lounge and lobby space. (Happy Cities)

Both buildings are built to Passive House standards, helping to improve energy efficiency—including a 56 per cent reduction in thermal energy demand—and reduce noise from the busy street out front.

Indoor lounge in the Timbre building, with large windows and doors opening onto the shared garden area. (Happy Cities)

Building more connected, affordable homes

The power of shared spaces is not just in whether a building has one, but in the decisions designers and housing providers make to increase the use of each space: locating them in frequently visited areas, adding features that invite use, supporting comfort and inclusion, and activating spaces with programming. In a multi-unit building, these shared spaces cost relatively little per resident—particularly when planned for in early design stages. In return, housing providers benefit from happier, healthier, more connected residents.

As Canada pushes to build affordable housing faster, designing for social connection can transform a roof overhead into a place that feels like home for the long term. With all actors on board—government, housing providers, designers, and funders—housing providers don’t have to make a tradeoff between sociability and affordability. Our homes can and should do both.

This article builds on a series of case studies published by Happy Cities, Hey Neighbour Collective, and SFU Renewable Cities as part of the Building Social Connections project. To learn more, visit the project web page.