What is placemaking? And more FAQs

How do you start a placemaking project, and why does placemaking matter for healthy communities? Happy Cities answers your questions!

A laneway in Downtown Vancouver, B.C. becomes a vibrant community space with seating, games, art, and lights. (Paper Crane Creative / Binners Project)

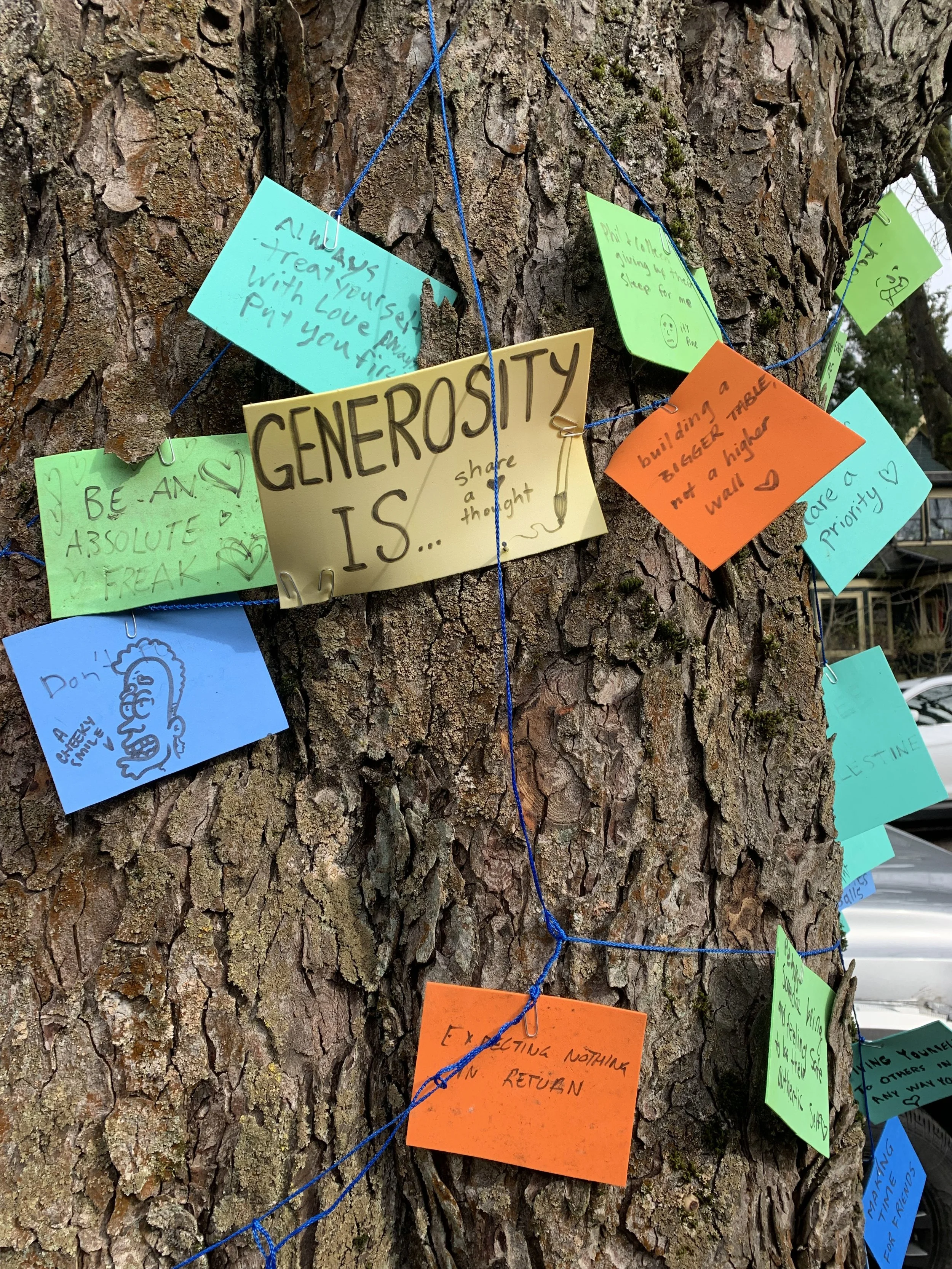

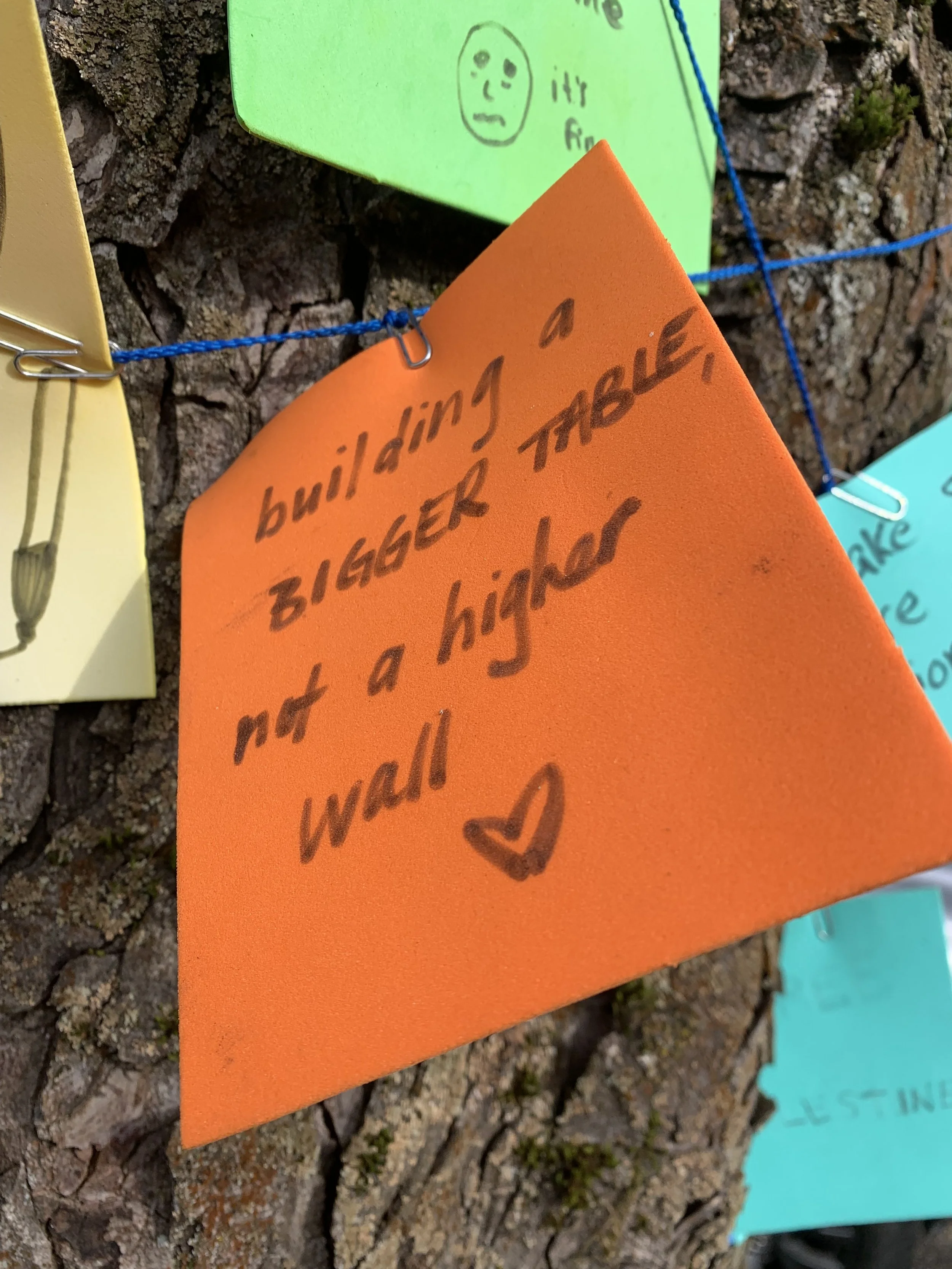

All it took was string, some clothespins, a pile of paper, and an old mailbox.

On a quiet street in Vancouver, there’s a string tied between two trees. Colourful pieces of paper are attached with clothespins, and more can be found in a mailbox attached to one of the trees. Above the mailbox is a prompt: “What are the little things/treats that get you through the day?” Neighbours have written answers on paper cards—everything from “my dog” to “pizza.” Every so often, someone changes the prompt, inviting new answers from the community.

A small installation of string and hand-written notes helps create a sense of place at the intersection of 10th Ave. and St. George Street in Vancouver. (Michelle Gagnon-Creeley)

This joyful little nook offers more than just a string and some paper: It adds joy to a stroll around the neighbourhood and invites interaction, prompting people to pause and linger. It creates a sense of place, differentiating this street corner from the many others nearby. And it exists because community members took the initiative to start it, and to care for it.

It’s a small example of the remarkable power of placemaking. Read on to learn more about what placemaking is, why it matters, and how to get started on your own project.

What is placemaking?

In our work with Canada’s Placemaking Community, we defined placemaking as community-led or -supported initiatives that aim to improve a place. Placemaking projects often aim to build community connections or address a local challenge, whether by creating a gathering space, building a garden to combat food insecurity, or painting street murals to improve safety.

This article focuses primarily on community-led placemaking. However, placemaking can also be led by professionals at larger organizations—such as a public plaza designed by a municipality or a developer, or a festival organized by a business improvement association.

Regardless of who initiates a project, the most successful placemaking involves community members and local residents in initiating, shaping, and stewarding a shared space.

What does placemaking look like?

Placemaking comes in many shapes and sizes. These projects may include murals, benches, community gardens, open streets, events, activities, and much more. What’s most important about these spaces is that people feel safe, comfortable, and connected in them.

Placemaking can be small:

A little library

Chalk on a sidewalk

A boulevard garden

Chairs in a park

Placemaking can also be big:

Removing a highway to restore a buried stream

Turning parking lots into urban farms

Painting large murals on buildings

Transforming trails into skateways in the winter

Who is a placemaker?

Anyone can be a placemaker. Maybe your next door neighbour is a placemaker—even if they don’t call themselves one! Many projects start when someone sees a problem in their neighbourhood and has a creative idea to solve it.

For example, a student at Glenbrook Middle School was worried about cars driving too fast near her school and wrote a letter to the City of New Westminster to help make the streets safer. Happy Cities worked with the students at Glenbrook to figure out ways to make the area around their school safer. The solution? Painting bump-outs in a design created, chosen, and painted by the students.

Students from Glenbrook Middle School paint curb bump-outs on the street to slow down traffic and improve safety. (Jared Korb / Happy Cities)

When Vancouver experienced record-breaking heat in 2021, the City had also restricted access to cooling stations and water fountains to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. In response, community members throughout Vancouver placed coolers filled with cold beverages and ice outside their homes, in parks, and near bus stops. Local businesses donated ice, and other community members filled the coolers with bottled water and other drinks. Through this community effort, Mount Pleasant Mutual Aid organized over 20 coolers during the heat dome, offering cold water and drinks for anyone in need.

Community coolers were distributed throughout Vancouver neighbourhoods during the 2021 heat dome. (Mount Pleasant Mutual Aid)

What are the benefits of placemaking?

Together with Canada’s Placemaking Community, we compiled evidence and stories on the power of placemaking to improve communities. Connecting with placemakers from coast to coast, we identified six key ways that placemaking benefits individuals and communities alike:

Placemaking improves mental and physical health.

Placemaking stimulates local economies.

Placemaking helps to build resilience, particularly during climate and emergency events.

Placemaking can help build a community’s identity and sense of belonging.

Placemaking makes people feel safer in their neighbourhoods.

The more people are involved in shaping the world around them, the more connected they feel to their neighbours and neighbourhoods.

Excerpts from the power of placemaking snapshots, collecting evidence and stories on how strengthens community wellbeing.

How much can placemaking cost?

Placemaking can take many shapes and sizes, and the costs depend on what the project involves—for example, materials, staff or volunteer time, or programming. In most cases, placemaking is one of the most cost-effective ways to address community challenges at a local scale.

The Brewery Creek Community Garden received a Neighbourhood Small Grant to host a community party in Vancouver. This is one of many examples of community projects that the program supports. (Michelle Gagnon-Creeley)

For some projects, the community is able to pool together the resources it needs and find volunteers to get the project started. In other cases, the project will need help from local businesses, the municipality, or another organization to get started.

For example, a community garden in Vancouver, B.C. wanted to grow a new pollinator garden and host a party where members could learn more about native pollinators and connect with neighbours. Thanks to a Neighbourhood Small Grant of $500, the garden members were able to purchase pollinator-friendly plants, host an expert talk, and buy some food to host the community.

Larger projects usually need longer-term funding commitments from municipalities or other organizations. However, even big placemaking projects cost relatively little compared to overall municipal budgets.

The City of Vancouver recently announced that the plaza at the intersection of Cambie Street and 18th Ave. will become permanent. The plaza was one of the first pilot plazas in the city. (Happy Cities)

For example, the City of Vancouver’s Neighbourhood Plaza program has transformed 27 street blocks into temporary pop-up plazas. The temporary plazas cost the City between $25,000 to $30,000 each—enough to add paint, greenery, and comfortable furniture to make the plazas welcoming. After seeing all the support for and use of the plazas, the City decided to invest in long-term infrastructure for five of them, with permanent road closures, public washrooms, and more. The permanent plazas are expected to cost $3 to $4 million each.

An outdoor movie night at Newton Athletic Park. (City of Surrey)

In Surrey’s Newton neighbourhood, residents had long expressed concerns about feeling unsafe in public spaces. Community members began to reclaim the neighbourhood by organizing activities and beautifying public spaces. Inspired by this, the City of Surrey created a placemaking action plan, adding better lighting, new public art, and even hosting community picnics and movie nights—all within a remarkably small budget of $2.4 million (for comparison, a new community centre in Newton will cost over $300 million).

I want to be a placemaker! How can I get started?

Anywhere, anytime! If you’re curious about being a placemaker here are some steps to get started:

Step 1: What is already happening in your community?

Start by looking at what is already happening in your neighbourhood, and if there are ways to get involved. For example, help out at a community garden, volunteer at a block party, or bring food to your community pantry.

Step 2: Identify something you would like to see more of in your neighbourhood or what your community might be needing extra support with.

Maybe you’ve noticed that your local park could use some extra furniture, or that you live in a food desert where your neighbours could benefit from a community pantry or fridge. The sky’s the limit!

Step 3: Identify where this might take place.

Step 4: Connect to resources.

Once you have an idea of a project, here are some sources or partners to consider for funding and other means of support:

Local businesses: Sometimes local organizations or businesses are able to donate directly to a project if it benefits the neighbourhood—all you have to do is ask!

Community organizations: Local organizations may have funding specifically for placemaking projects. For example, there is a network of neighbourhood small grants available across B.C. on an annual or seasonal basis provided by community foundations.

Municipalities: Municipalities sometimes offer small grant streams for placemaking projects, and sometimes they’re organized by theme. In Vancouver for instance, the City offers funding for community placemaking.

How can you measure the benefits of placemaking?

Happy Cities’ Public Life Study tool is a free resource that anyone can use to measure social inclusion, trust, and connection in public spaces

Inspired Art Impact: Main Street Toolkit — STEPS Public Art

Building better public spaces: A toolkit to create a Public Space Inventory — Evergreen

Place Standard Tool — Our Place

Open Streets Toolkit — 880 Cities and Street Plans

A New Bottom Line: The Value & Impact of Placemaking — Toronto Metropolitan University

Can you think of a spot that fits the bill? Play our placemaking bingo!

Eager to find more examples of placemaking in your community? We’ve made a bingo card with some of the telltale signs of placemaking. Print this out or screenshot it to play! And don’t forget to email us with your results, or post them and tag us on Instagram or LinkedIn!

Want to learn more? Check out some of our placemaking resources:

Resources and tools

Toolkit for placemakers — Canadian Urban Institute

Public life study tool — Happy Cities

Pavement to plaza wellbeing assessment — Happy Cities

Power of placemaking: community snapshots — Happy Cities & Canadian Urban Institute

Toolkit for rapid placemaking to bring back Main Street — Canadian Urban Institute

Reimagining public spaces suite of toolkits — Evergreen

The CultureHouse handbook: How to create a pop-up community space — CultureHouse

Talks

Creating Happier Cities from the Ground Up with Emma Avery and Leah Karlberg — Cities for Everyone with Gil Penalosa

Building the Case for Placemaking: What Is It and Why Does It Matter?

Rapid Placemaking for Main Streets — CUI City Talks

The Power of Placemaking: Evidence and stories on wellbeing with Mitchell Reardon and Leah Karlberg — CUI City Talks

A conversation with Happy Cities about building back "Main Street" with Mitchell Reardon and Emma Clayton-Jones — SFU Office of Community Engagement

Social Cohesion Through Placemaking with Leah Karlberg — Brand Battle for Good: Understanding Isolation Conference

The City is the People with Mitchell Reardon — Evergreen Resource Hub

Designing Happy Cities with Mitchell Reardon — Shared Space Podcast

Creating Happiness with Mitchell Reardon — Amazing Places Podcast