Las Vegas: An unlikely model for walkable suburbs?

How do you transform a suburb into a walkable place? Las Vegas is betting on “catalytic redevelopment”—creating one great place that people love spending time in.

Conceptual rendering of a people-friendly local street in Charleston, Las Vegas. (Happy Cities / City of Las Vegas)

By Emma Avery, Houssam Elokda, and Tristan Cleveland

Charleston is a large area west of Downtown Las Vegas, home to over 75,000 residents. Over the next 25 years, the City of Las Vegas is taking on a big challenge: Can it transform Charleston and other neighbourhoods into walkable, transit-oriented places that improve quality of life for residents? The recently adopted Charleston 2050 plan outlines a roadmap to get there.

Why does walkability matter for Las Vegas?

Vegas is a sprawling city that has been expanding outwards ever since the Strip (which falls under a separate jurisdiction from the City of Las Vegas) took off around the 1940s. It embodies the era of car-dominance in which it was built: a collection of residential neighbourhoods divided by wide, fast-moving roads and strip malls.

Major arteries through Charleston consist of wide, fast roads spanning up to eight lanes, with large intersections and little protection for pedestrians or bikes. (Happy Cities)

Many people love Charleston. But it’s also a challenging place to live.

“We don’t walk to the grocery store, even though if I threw a ball I could probably hit it,” one resident told us. “But with the traffic and getting across the street, it’s too difficult.”

Previous design choices have hurt quality of life for residents. Over several visits to Charleston, we saw kids biking to school or waiting for the school bus in the hot sun, with little to no protection from fast-moving traffic. We saw people running across eight-lane roads because there are no crosswalks for hundreds of metres. All of Charleston’s major roads are part of the City’s “high-injury network,” where the City’s most severe traffic collisions occur.

A young person skateboarding in a bike lane in Charleston. (Happy Cities)

A child walking to school next to a large parking lot in Charleston. (Happy Cities)

The City recognizes a need to invest in making suburban neighbourhoods healthier, more attractive places to live, work, and play—particularly as tourism has been slowing. Its ambitious 2050 Master Plan outlines goals to create more homes, safer streets, and mixed-use activity centres across the city. The regional transit authority is planning to add more high-capacity bus service on major corridors. The City of Las Vegas wants to become a great place to live in its own right—not just a bedroom community for the Strip.

The design ingredients for a walkable, human-centred place

Research shows that neighbourhoods need several ingredients to encourage people to walk and take transit:

Safe streets

Short blocks

Efficient transit

Greenery

Public spaces

Compact, mixed-use buildings

When neighbourhoods have these essential ingredients, residents are more likely to be happy, healthy, connected, and trusting of their neighbours—and government. There is wide agreement on the ingredients for walkable places, and support for this kind of design in the Las Vegas 2050 Master Plan. But cities often struggle to envision how to get there.

How to transform the suburbs for walkability

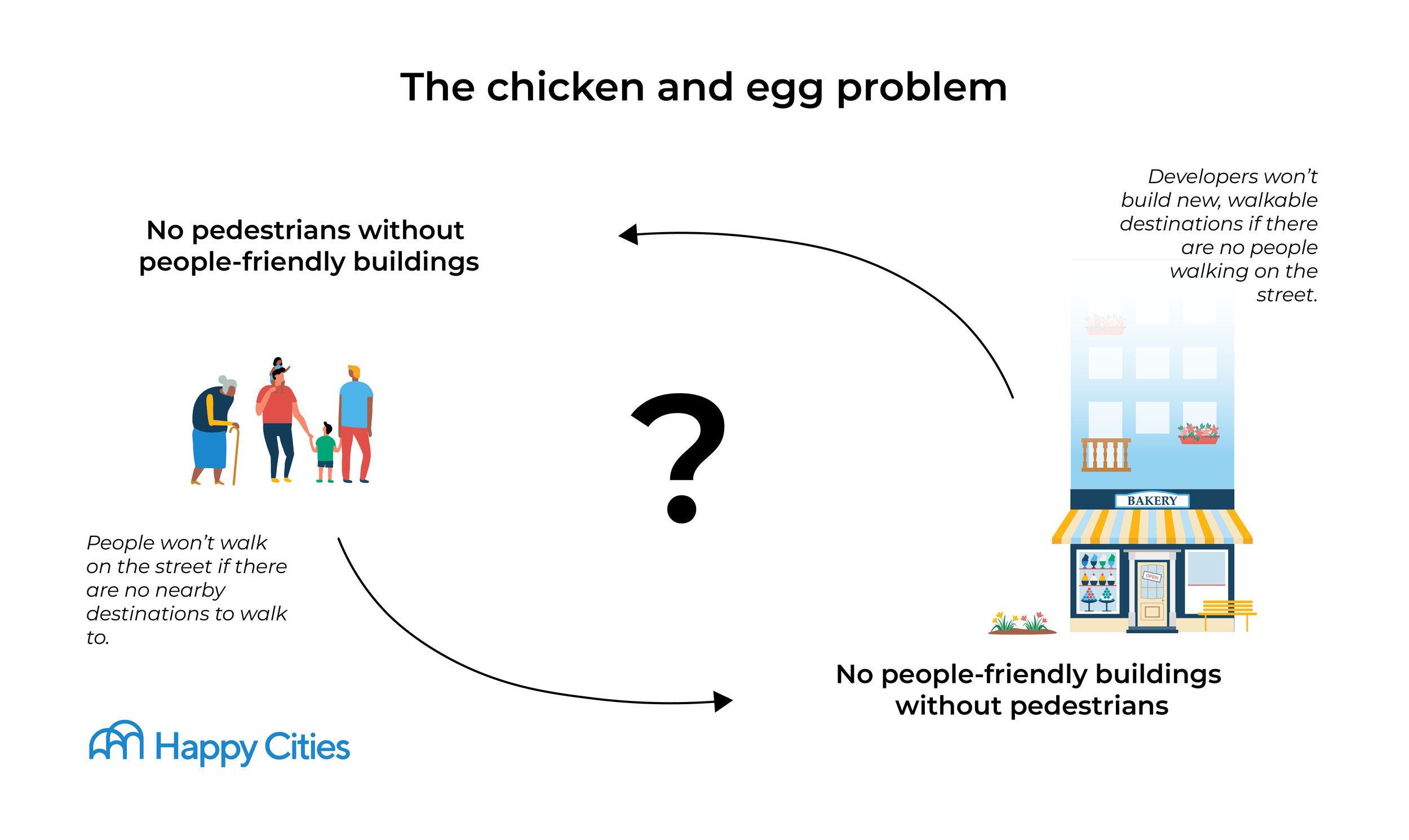

Las Vegas has, in the past, struggled to attract pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use development outside of Downtown. Compact businesses and homes generate more revenue than a big-box store with a parking lot, but they also cost more to build. Developers told us that they can’t charge enough per square foot in suburban areas to make mixed-use projects viable. By itself, rezoning is unlikely to lead to any change in Charleston.

The Charleston plan proposes three practical steps to overcome this challenge:

Start with one great block: Identify the locations where people-friendly development is most likely to succeed, and concentrate efforts there

Incentivize people-friendly places: Create a time-limited development program to enable people-friendly projects in a specific area

Invest in a great public realm: Upgrade streetscapes and build new community spaces to create a place that people love

Here’s how it works.

1. Start with one great block

Investments have a bigger impact when concentrated together rather than spread all over the place.

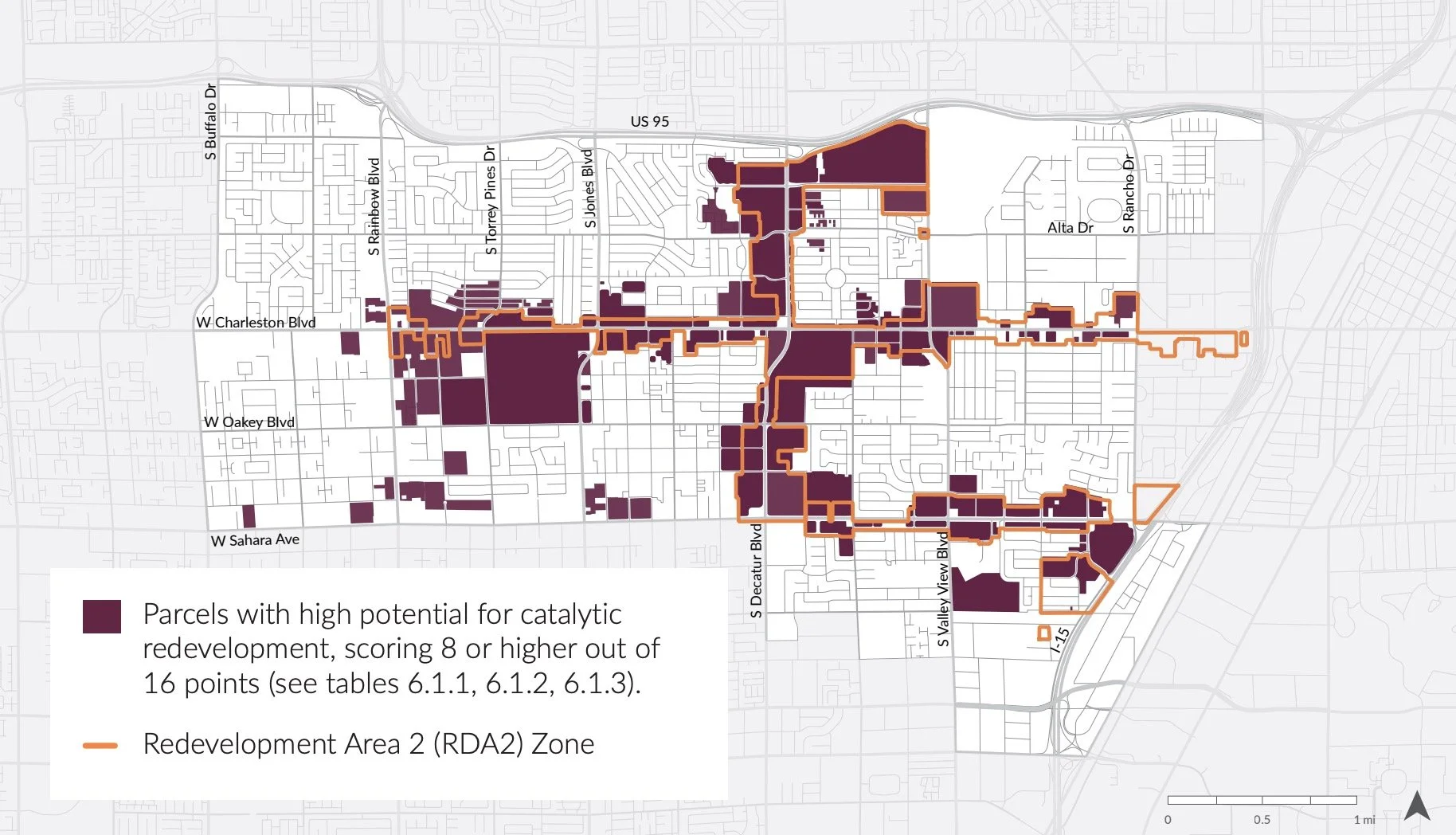

The Charleston plan identifies key areas for “catalytic redevelopment,” where the City will prioritize large-scale investment in walkable places. The idea is to concentrate human-scaled development in one great place: a safe street or public area surrounded by new buildings rather than large parking lots, where it is possible to attract cafés, restaurants, shops, and people.

New public infrastructure and mixed-use developments work together to attract both visitors and residents. In turn, this raises the value of nearby lots, making mixed-use projects financially viable.

In other words, a great place helps establish the street life and economic conditions necessary to support many businesses and homes. Once such a place exists, it will be easier to convince other developers to build more, similar projects nearby, which helps catalyze a longer-term transformation.

A map indicating the areas with the greatest potential for catalytic redevelopment projects, including those in close proximity to transit, parks, and major destinations, and areas the City has already identified for redevelopment. (Happy Cities / City of Las Vegas)

2. Incentivize people-friendly places

Once strategic areas for redevelopment have been determined, time-limited incentives help cities overcome the ‘first mover’ problem, by making mixed-use developments financially viable, and by encouraging multiple developers to build at the same time.

Strategic policy and incentives can help cities overcome the challenge of initiating walkable development in suburban areas. (Happy Cities)

During engagement, we heard the kinds of policy changes that would help encourage local developers to build something more than a strip mall: things like faster approvals, financial incentives for good design, and parking reductions. The plan also explores the potential for a self-sustaining municipal loan program, like Salt Lake City has done.

The Arts District, closer to Downtown Las Vegas, shows what this transformation might start to look like in 10 years.

Las Vegas’ Arts District recently underwent a revival thanks to municipal investments in streetscaping. (Happy Cities)

3. Invest in a great public realm

Once the groundwork has been laid for a great place, Las Vegas will need to support a vibrant, people-friendly streetscape through tools such as:

Human-oriented design guidelines for new developments

Street upgrades to improve comfort and safety

Investments in new community facilities

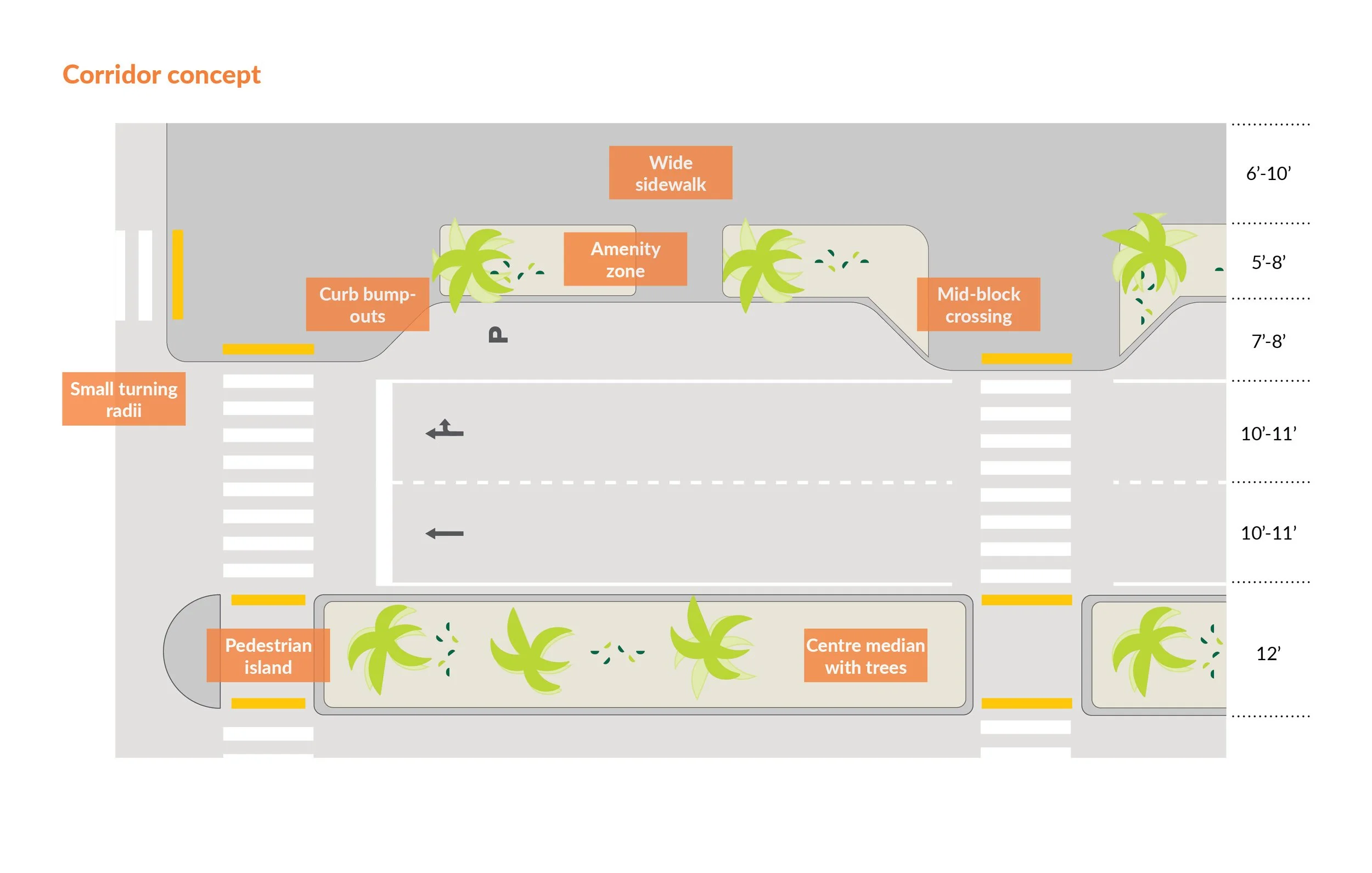

For example, Charleston is defined by its wide roads, sometimes up to 100 feet wide.

“People ignore the speed limit and drive their cars fast down the street,” one person wrote in our public survey. “There needs to be acknowledgment that we are not in a freeway or Grand Prix! The young and old need to be safe!”

The wide, fast roads pose major barriers to walking and rolling. But they also offer opportunities—space to build wider sidewalks, safe bike paths, bus lanes, and tree-lined medians.

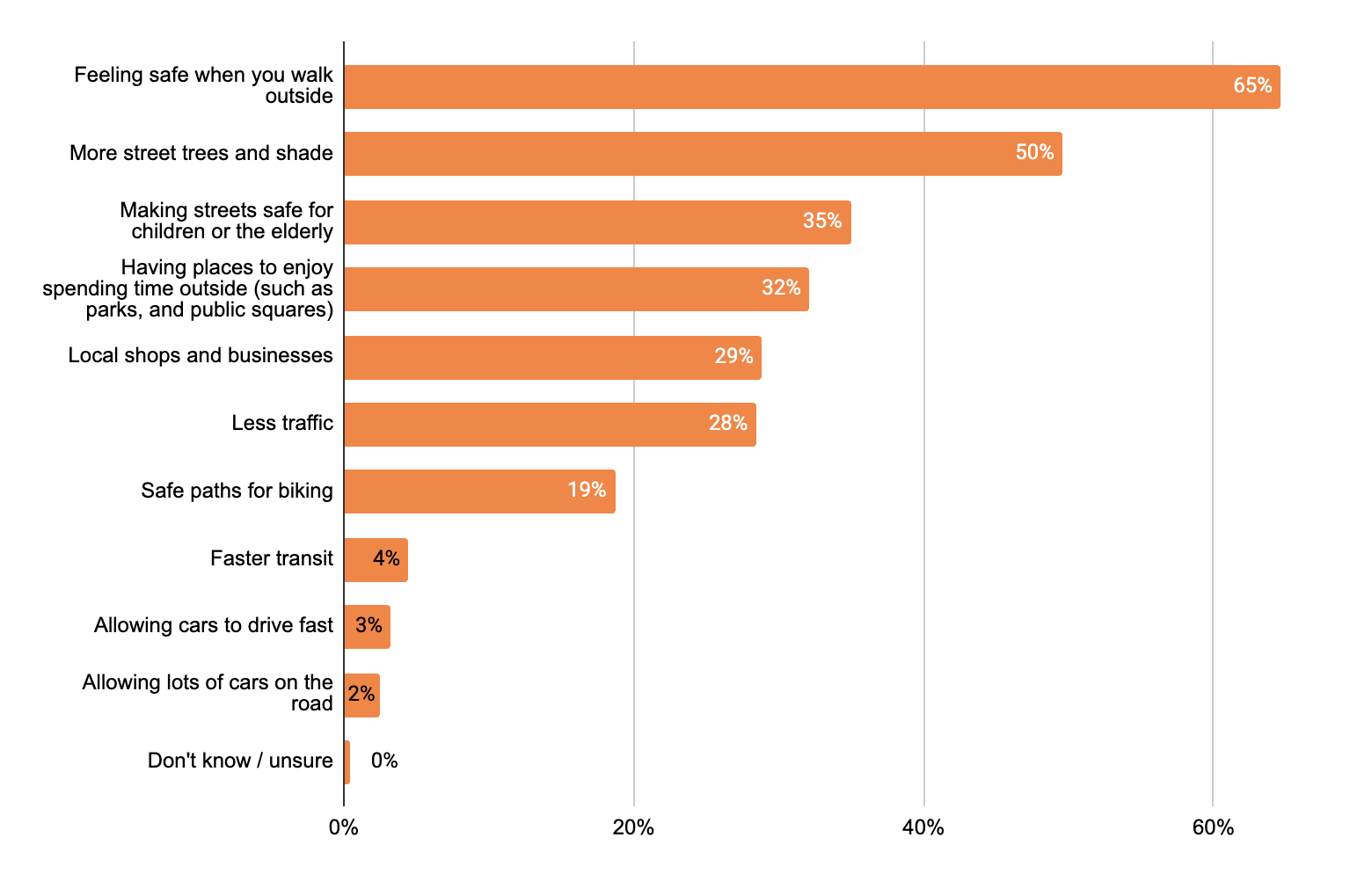

Cities sometimes assume that driving places is a top priority for residents. But when we asked people, driving ranked much lower than a safe, comfortable, inviting public realm. The overwhelming street design priority was “feeling safe when you walk outside.” Almost no one selected allowing cars to drive faster, or allowing more cars on the road.

Charleston residents picked their top three priorities for streets in their neighbourhood in an online survey (results shown above) and at community pop-up events. (Happy Cities / City of Las Vegas)

Building on best practices and Las Vegas road standards, we suggested conceptual redesigns of corridors. Charleston won’t become walkable overnight. But the plan outlines a roadmap for the City to prioritize street upgrades, concentrating these in catalytic redevelopment areas and along the most important routes for pedestrians to maximize the impact of public investments.

Torrey Pines Drive today, a wide road that passes by several schools in Charleston. (Google Streetview)

Conceptual rendering of what Torrey Pines could look like with wider sidewalks and safe paths for biking. (Happy Cities / City of Las Vegas)

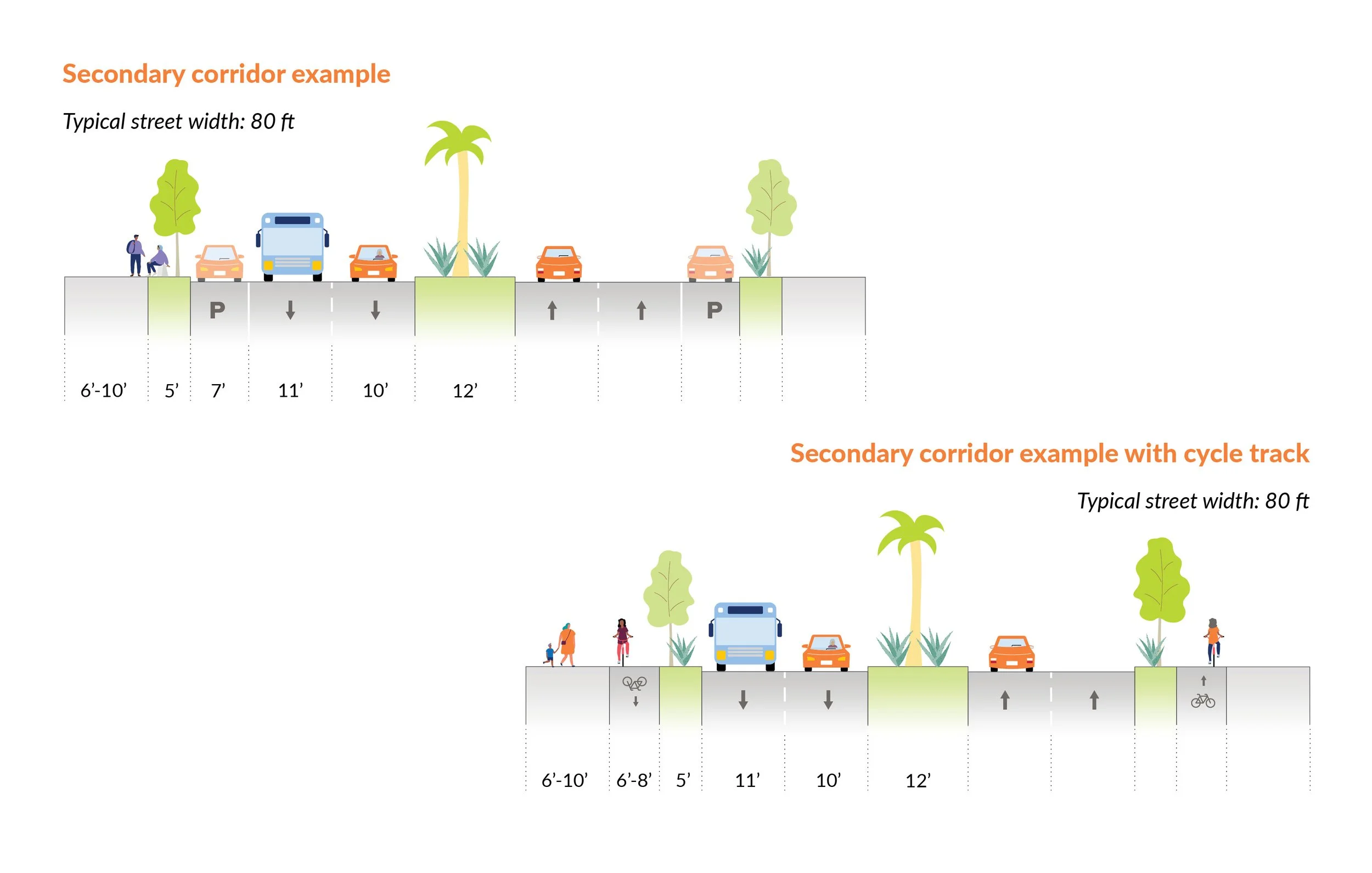

The Charleston plan also outlines clear design standards for different types of streets. Major corridors should prioritize efficient travel for commutes, while local streets and secondary corridors should prioritize active travel and pedestrians. By establishing clear standards, cities can make commuting better for all modes.

Creating a place that people can believe in

Ultimately, the success of the Charleston plan will depend on whether it can create the conditions for a human-scaled transformation to succeed—in, other words, a place that people can believe in.

As one resident asked in a focus group, “How do you have pride in your community if you aren’t proud of what it looks like?”

Change won’t happen overnight. It will take steady, focused investments in the hardware—safe streets, parks, affordable housing options, places to gather—but also the software: clear policies and design guidelines to encourage the types of transformation that residents want to see, and concentrating change in strategic areas. There must be accompanying policies to maintain and build affordable housing, to ensure that community members can benefit from this growth.

A single great block—a vibrant oasis of street life with a mix of homes, local businesses, and gathering places—communicates that Charleston is a place people want to spend time in, a place to invest in building a more resilient, connected future. Over time, this transformation can snowball outwards, paving the way for a community that people are proud to call home.

Local streets in Charleston have ample space for wider sidewalks, new vegetation, and gentle density to offer more housing choices while maintaining neighbourhood character. (Google Street View, Happy Cities / City of Las Vegas)